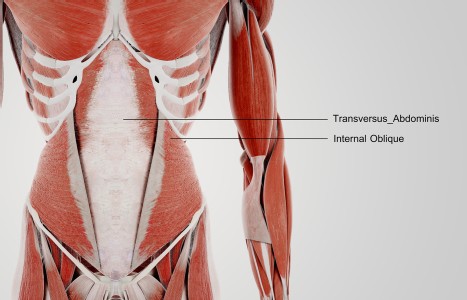

TrA-2, my primary needle location, I needle 95% of the time and I think it works the best. You’ll know you have the right point location when you discover the muscle twitching when applying electric stimulation.

A Slippery Situation

The "Ask Dr. Jiang" column is designed to explore corners of Chinese medicine that may not be easily understood by American practitioners or are underrepresented in American clinical health literature.

There are several popular English-language books that list the pulse quality for Stomach fire as "slippery." Since the other signs of this pattern include constipation, dry mouth and dry tongue coat, I'm assuming that the slippery pulse is not intended here to reflect a complication of dampness or food stagnation. That being the case, why, then, would Stomach heat cause a slippery pulse? Could this be a mistake in the books?

Trying Not to Slip Up

New York, New York

Dear Trying Not to Slip Up:

No, it's not a mistake. The pulse for Stomach fire is slippery. The problem is that the English-language books I have read list dampness, phlegm and food stagnation as the only possible indications for the slippery pulse (hua mai). They fail to mention that excess heat can itself cause a slippery pulse, even in the absence of these other pathogens. Stomach fire causes a slippery pulse because it is an excess heat pattern.

The slippery pulse is one of the five yang pulses. It is described as smooth-flowing, "like pearls rolling in a dish." A slippery pulse is a normal sign when found in pregnant women or strong healthy people, where its fluid feel reflects the easy circulation of abundant qi and blood; however, in disease states, it is the abundance of pathogenic excess that gives rise to this same smooth-flowing characteristic. For this reason, pathogens such as food stagnation, dampness and phlegm, all "fluid" in nature, can easily impart a slippery quality to the pulse. However, excess heat can have the same effect, by increasing the yang fire in the body and propelling the qi and blood more quickly and smoothly through the vessels.

Dampness and phlegm are, in fact, more likely to cause a slippery pulse when they become damp heat or phlegm heat. Internal damp cold, for example, usually presents with a moderate (huan) or slow pulse, since this pattern tends to occur when there is pre-existing yang deficiency. Phlegm cold will often produce a wiry or tight pulse, because the obstructive effect of pathogenic cold tends to overshadow the slippery properties of phlegm.

According to the Shang Han Lun, the slippery pulse was one of the confirmations for bai hu tang (white tiger decoction), a formula used to treat yang ming channel disease (see, for example, page 70 of Bensky and Barolet's Formulas and Strategies). In this case, the slippery pulse is clearly reflecting excess heat, since yang ming channel disease is definitely not a form of dampness. In fact, one of the functions of bai hu tang is to moisten dryness caused by heat-damaging fluids.

Liver fire is identified by a pulse that is slippery and wiry, as is damp heat invading the liver and gall bladder. In the latter pattern, the slippery pulse combines with a greasy yellow tongue coat and other signs, such as nausea and jaundice, to confirm damp heat. But what about liver fire without damp heat? This pattern can have a slippery, wiry pulse as well, and in this case, the slippery quality is the result of the abundant excess heat present in Liver fire.

I hope this puts to rest the mistaken idea that the slippery pulse is only a sign of dampness, phlegm or food stagnation. If you forget that this pulse can also indicate excess heat, you can indeed "slip up" in your diagnosis!

Edited with the assistance of John Pirog, MSOM.