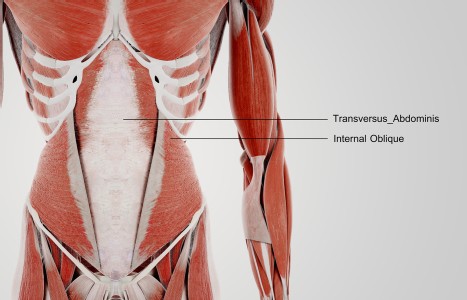

TrA-2, my primary needle location, I needle 95% of the time and I think it works the best. You’ll know you have the right point location when you discover the muscle twitching when applying electric stimulation.

Ethics of Asian Bodywork Practice, Part Two

In the first part of this article, I gave a brief overview on ethics, and outlined a course I give to my ABT and acupuncture students. In the second and final part of this article, we will examine a few useful case studies from the U.S., Canada and Europe. I've changed the names of the patients and practitioners to protect their privacy.

Case Study #1: "Simon"

Acupressure and movement therapist "Marty" observed bruises on the legs of her little eight-year-old patient, "Simon." Simon told her about the way his father beat him, but begged her not to say anything because he was terrified of the consequences: more brutality, a potential family split, and the possibility of being taken into foster care. Simon was building such a rapport and trust with Marty that she felt very torn about breaking his confidence, but was equally mindful of her obligations under state law. Eventually Marty consulted a social worker, who advised her to continue treating Simon until they could all reach a constructive and sensitive resolution. Simon's grandparents eventually took custody of the boy and his siblings.

Case Study #2: "Sonia"

"Sonia's" father "Josef" brought her to shiatsu therapist "Callie" for migraine relief. As Callie didn't live in the same country, she offered to teach Josef some techniques to help Sonia's pain. When Josef placed his hands on Sonia's shoulders, therapist Callie observed the teenager's reaction: a subtle shrinking away from her father's touch. On subsequent visits, Callie shared her observations with Sonia, who confirmed her father was, as she put it, "sexually curious" about her. As Sonia was over 18, and thus an adult, Callie decided, with Sonia's agreement, to talk to her parents to suggest family counseling in Sonia's best interests. Josef denied everything. Not only was Sonia's mother "Lisa" in equal denial, but she exploded with anger and accused Callie of interfering and trying to break up the family. Sonia eventually left home to attend college and carve a life for herself outside of the family structure. Years later, she enlisted the help of a family counselor to help repair the family rift. She has always been appreciative of Callie's support and caring.

Case Study #3: "Pete"

Acupuncturist "Miguel" called me in distress one day for advice. His patient "Pete" had arrived raging drunk the night before for a session. As Pete had prepaid a package of five sessions, he insisted it was his right to be treated. Miguel refused. There was an unpleasant scene. Miguel called a cab and asked the cab driver to ensure Pete got home safely. As it happened, Pete threatened the cab driver, and insisted he circle the block and drop him off in the acupuncturist's parking lot so he could drive his own car home. Moments later, Pete got in an auto accident. Miguel called me anxiously to ask if he was liable in any way. The answer was no. He had done all he could to ensure his patient returned home safely. In a similar future situation, Miguel could, perhaps, remove the patient's car keys from the key ring - or, if the situation gets really threatening, dial 911.

Case Study #4: "Famous Client"

In their excellent book Ethics of Touch, Ben Benjamin, PhD, and Cherie Sohnen-Moe1 write about the case of an acupuncturist who lost a lot of time (and thus money) making house calls to a "famous client." For several sessions, the acupuncturist had to sit around and wait while the famous client attended to "urgent" phone calls and other matters. Eventually, the acupuncturist started to charge for his time, thus sending the correct message to the client.

I have heard of similar cases where therapists give more leeway to famous clients than to Jack & Jill Average, only to regret it later. A tuina colleague of mine felt so flattered by a famous dancer who asked him for treatments backstage, he dutifully hung around, missed half the show, and then gave a quick 10-minute, unpaid, rushed "tune-up" to the dancer's shoulder. He left the theater vowing never to be caught in a similar trap again, without establishing some clear boundaries and fee structures up front.

Case Study #5: "Cozy Chuck" or "Cozy Connie"

Some students in student clinic have asked me for advice about patients who make "cozy" comments without directly "coming on" to them. "I feel really uncomfortable with Patient A," one anxious student told me, "and I don't know how to handle the situation." The patient's comments ran something like "This is our special time together", or "I know I'm one of your special patients."

My advice to the student was three-fold: A) make sure your student partner is in the room with you at all times; B) be very structured, professional, crisp and direct in your body language and choice of words with the patient; and C) don't enter into the "cozy" corner verbally, or try to dialogue with the patient about it. I also advised him to ask the student clinic to book the patient with another student for future visits, and use clinic policy about "mixing and matching" students and patients as an excuse.

Direct confrontation could lead to denials and embarrassing consequences in "cozy" cases. Generally, I tell students that when they are in professional practice, it's wise to refer such patients to a colleague with a particular specialization, in everyone's best interests. Of course, in situations where the overtures are blatant, we advise students to leave the room immediately and enlist the supervisor's help.

Case Study #6: Transference

A colleague who runs a group ABT practice came to me with a serious challenge. A new patient walked into her clinic one day and startled her, because he looked like her first love. Outwardly she acted with a thoroughly professional manner, but inwardly she admitted her heart was beating rapidly, and it was difficult to be objective when treating the guy. We spoke about the importance of using qi shields and visualization to ensure detachment in future sessions, but the experience so unsettled her that she referred him to a colleague.

Another colleague of mine spoke about a patient who kept telling him he reminded her of her father. The colleague found himself slipping kindly, though unconsciously, into this role, giving fatherly advice that went beyond his role as a shiatsu therapist. Eventually, when he realized what was going on, he referred her to a chiropractor for her back problems and told her she required a "more advanced" form of treatment, in her own best interests. He feels he learned a valuable lesson from the experience, and knows how to recognize similar signals in future.

To sum up, it is always wise, when in doubt, to consult a former teacher, or a colleague with more experience, when confronted by a challenging situation. Both www.aobta.org and www.nccaom.org have useful codes of ethics on their Web sites, which are good to display in a prominent place in a group practice.

Forward in qi ...

Reference

- Ethics of Touch by Ben Benjamin, PhD, and Cherie Sohnen-Moe. 2003. ISBN #1-880908-40-6.