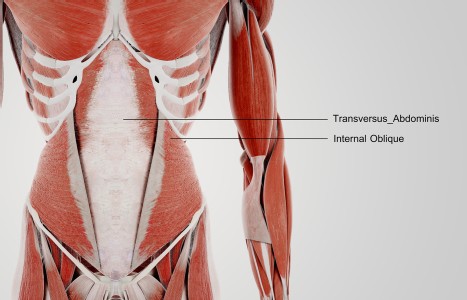

TrA-2, my primary needle location, I needle 95% of the time and I think it works the best. You’ll know you have the right point location when you discover the muscle twitching when applying electric stimulation.

Ovarian Cysts and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

An ovarian cyst is an abnormal collection of fluid (clear or bloody) with a thin wall that can appear in or on an ovary.1 They range in size from 2 mm to greater than 10 cm; from the size of a pea to a cantaloupe. They are almost always benign, and most premenopausal women will develop them. Many cysts go away by themselves, or shrink and expand with the menstrual cycle. Fifteen percent of postmenopausal women will also develop them. Herbalists will see patients when they complain of pain or unusual bleeding.

Functional cysts appear during ovulation and include follicular, corpus luteum and hemorrhagic. The follicular cyst forms when a follicle doesn't rupture to release an egg. It becomes fluid-filled and quite large, over 6 cm (2.3 inches). If it ruptures, it can cause severe pain, usually during ovulation. These cysts often disappear by themselves over three to four months. Chinese herbal medicine can accelerate the process of reduction and removal.

Corpus luteum cysts appear after the ovary has released the egg. The follicle then becomes a secretory gland known as the corpus luteum. Normally, a ruptured follicle produces quantities of estrogen and progesterone after rupturing to facilitate pregnancy, and gradually breaks down and disappears if pregnancy doesn't occur. In the case of a corpus luteum cyst, it fills with fluid or blood, often unilaterally, usually without pain. At some point, within three to four months, it will rupture during menstruation and disappear naturally. The drug Clomid (clomiphene citrate), used to induce ovulation in fertility treatments, can induce corpus luteum cysts, as can taking progesterone. Birth control pills, on the other hand, can prevent or treat these cysts. In some cases, the corpus luteum cyst can grow quite large (10 cm), and has the potential to cause bleeding, or twist the ovary or fallopian tube and cause sharp pain. In these cases, Chinese herbal medicine can accelerate reduction and removal of the cyst, although sometimes surgery is required.

The hemorrhagic cyst is a blood cyst, where small blood vessels have broken and allowed blood to fill the cyst. These cause unilateral abdominal pain, often on the right side. If it ruptures, (which is rare), the blood fills the abdominal cavity and is quite painful. If it doesn't rupture, it usually resolves by itself without surgery.

Organic ovarian cysts include endometrioid cysts and polycystic ovaries. Women with endometriosis can develop endometrioid cysts, also known as chocolate cysts. In this case, uterine endometrial tissue sloughs off, transplants and grows inside the ovary. Blood will build up over months or years and if it bursts, coagulated blood spills throughout the abdominal cavity. The medical approach is use of NSAIDs and anti-ovulatory drugs such as birth control pills.

Polycystic ovaries present an enlarged ovary with multiple cysts on the surface. These cases often developed when there is increased testosterone and insulin resistance, and are a significant cause of infertility. They also carry an increased risk for endometrial cancer.

Ovarian cysts of any type can appear with a number of symptoms, including dull or aching lower abdomen, breast tenderness, menstrual pain, irregular menses, abnormal uterine bleeding or spotting, frequent urination, nausea, fatigue, infertility and increased facial or body hair. When a patient with any of these complaints comes to the clinic, the herbalist should consider the possibility of an ovarian cyst, and recommend medical diagnosis for confirmation.

Most ovarian cysts are treated with a "wait and see" approach after diagnosis with ultrasound, or with treatments for pain. For postmenopausal women or menstruating women experiencing symptoms for more then three months, diagnosis to rule out ovarian cancer is important. Diagnosis is with CT scan or laparoscopy. In questionable cases, surgical removal is recommended.1

TCM describes all types of ovarian cysts as enlarged ovaries. It is seen as a consequence of water accumulating in the abdominal cavity where it transforms into phlegm, usually as a result of kidney yang deficiency. There may often be coexisting blood stagnation or liver qi stagnation. The treatment principle, depending on clinical signs and symptoms, is to tonify kidney yang, transform phlegm, benefit the movement of water, dredge or move liver qi, invigorate blood and break blood stasis. This approach is performed regardless of the type of cyst, or whether it involves polycystic ovaries.

Dr. Yu Jin, in her excellent book on obstetrics and gynecology, recommends the following general formula (Table 1).2

| TABLE 1 | |

| shu di huang (Radix rehmanniae glutinosae preparata) | 12 g |

| shan yao (Radix dioscoreae oppositae) | 12 g |

| huang jing (Rhizoma polygonati) | 12 g |

| yin yang huo (Herba epimedii) | 12 g |

| bu gu zhi (Fructus psoraleae corylifoliae) | 12 g |

| chuan shan jia (Squama manitis pentadactylae) | 9 g |

| zao jiao ci (Spina gleditsiae sinensis) | 12 g |

| chuan bei mu (Bulbus fritillaria cirrhosa) | 12 g |

| dang gui (Radix angelica sinensis) | 12 g |

| tao ren (Semen persicae) | 12 g |

With signs of cold, add 9 g fu zi (Radix lateralis Aconiti sarmichaeli praeparata) and 3 g rou gui (Cortex cinnamomi cassiae). With constrained liver qi, omit zao jiao ci and chuan bei mu. Add 9 g mu dan pi (Radix cortex moutan), 12 g zhi zi (Fructus gardenia jasminoides), 6 g chai hu (Radix bupleurum)and 6 g qing pi (Pericarpium citri reticulatate viride).

Case Report

Monica, 38, came to the clinic with an ultrasound diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). The three largest cysts measured 7 mm, 6 mm and 5 mm. She had a history of Hashimoto's thyroiditis, some depression and PMS. She also showed elevated insulin, blood sugar and cholesterol, and was prescribed metformin (Glucophage). She had been on levothyroxine (Synthroid) and was now on Armour thyroid. We began a course of acupuncture (Japanese meridian-balancing) twice monthly for several months. Initially, I used Dr. Jin's recommended formula prepared as an alcohol extracted tincture. I added bai jie zi (Semen brassicae) and substituted lu lu tong (Fructus liquidambaris) for chuan shan jia, and continued this formula for two months. In September, she complained of menstrual cramps, and I had her take Tong Jing Wan for three days prior to menses until cramps ceased.3 She reported that this had good effect, and we followed that routine for several months.

Her menstrual cycles were the main guide to adjusting her formula. She reported ovulatory pain on the right side. Her periods were preceded by light spotting for several days, followed by four days of normal bleeding. Tong Jing Wan controlled her cramps, and I decided to include some of those herbs into her formula. The adjusted formula is in Table 2:

| TABLE 2 | |

| huang jing (Rhizoma polygonati) | 10 g |

| yin yang huo (Herba epimedii) | 8 g |

| bu gu zhi (Fructus psoraleae corylifoliae) | 9 g |

| zao jiao ci (Spina gleditsiae sinensis) | 8 g |

| dang gui (Radix angelica sinensis) | 9 g |

| tao ren (Semen persicae) | 9 g |

| bai jie zi (Semen brassicae) | 9 g |

| sha ren (Pericarpium amomi) | 8 g |

| zhi ke (Fructus citrus aurantium) | 8 g |

| e zhu (Rhizoma curcumae zedoariae) | 9 g |

| lu lu tong (Fructus liquidambaris) | 8 g |

| ji xue teng (Radix et caulis millettiae) | 9 g |

| tao ren (Semen persicae) | 9 g |

| san leng (Rhizoma sparganii stoloniferi) | 8 g |

This formula controlled her cramps and reduced premenstrual spotting. I switched her to a prepared formula, Seven Forests, which has a similar composition, and was easier for her to take. The dosage was three tablets twice daily. That formula is in Table 3:

| TABLE 3 | |

| shu di huang (Radix rehmanniae glutinosae preparata) | 15 g |

| huang jing (Rhizoma polygonati) | 10 g |

| lu jiao jiao (Cornu cervi gelatinum) | 9 g |

| rou gui (Cortex cinnamomi cassiae) | 9 g |

| bu gu zhi (Fructus psoraleae corylifoliae) | 9 g |

| bai jie zi (Semen brassicae) | 9 g |

| chuan bei mu (Bulbus fritillaria thunbergii) | 9 g |

| kun bu (Thallus algae) | 9 g |

| tao ren (Semen persicae) | 7 g |

| e zhu (Rhizoma curcumae zedoariae) | 7 g |

| san leng (Rhizoma sparganii stoloniferi) | 7 g |

The patient continued this product for several months. On follow-up ultrasound, no cysts were found on the ovaries, and herbs were discontinued. Her blood work showed improved cholesterol and normalized blood glucose but her testosterone was climbing. I was concerned about a return to an abnormal PCOS differentiation and gave her a formula to address possible cyst formation that would also address deficiency of kidney yin, incorporating liu wei di huang wan. We kept her on this formula for several months in tincture form (Table 4):

| TABLE 4 | |

| shan yao (Radix dioscoreae oppositae) | 9 g |

| huang jing (Rhizoma polygonati) | 10 g |

| dang gui (Radix angelica sinensis) | 10 g |

| shu di huang (Radix rehmanniae glutinosae preparata) | 14 g |

| yin yang huo (Herba epimedii) | 10 g |

| chuan bei mu (Bulbus fritillaria cirrhosa) | 9 g |

| mu dan pi (Radix cortex moutan) | 9 g |

| ze xie (Rhizoma alismatis orientalis) | 10 g |

| fu ling (Sclerotium poria cocos) | 12 g |

| tao ren (Semen persicae) | 10 g |

| shan zhu yu (Fructus corni officinalis) | 9 g |

Chinese herbal medicine is very effective for treating functional ovarian cysts with accumulations of fluid or blood. In cases of PCOS, treatment is more complicated and takes longer, but I believe that it is treatable.

References

- Ovarian Cyst. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ovarian_cyst

- Jin Y. Handbook of Obstetrics & Gynecology in Chinese Medicine, An Integrated Approach. Seattle:Eastland Press, 1998, p. 60.

- Fratkin JP. Chinese Herbal Patent Medicines: The Clinical Desk Reference. Boulder, Colo.: Shya Publications, 2001, p. 549.