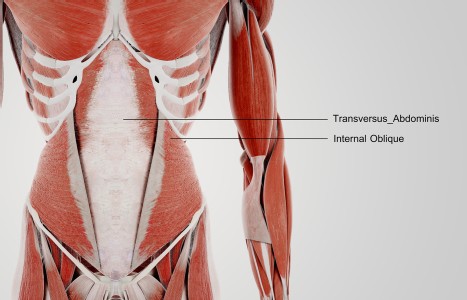

TrA-2, my primary needle location, I needle 95% of the time and I think it works the best. You’ll know you have the right point location when you discover the muscle twitching when applying electric stimulation.

We Get Letters & E-mail

The TCM vs Five-Element Acupuncture Divide

I just wanted to comment about the article: "The TCM Vs Five-Element Acupuncture Divide." I value the article written by the patient Constance Scharff regarding the TCM and Five-Element style split. I agree it is more important to be a unified profession and have a strong national voice, but as a long-term practitioner, this issue has befuddled us for decades and needs to be finished. As far as her experience with the TCM acupuncturist helping her to heal dramatically but not engaging in much conversation or counseling; well, what can you expect when someone has a very busy practice. Not all TCM practitioners work like that. Many prefer to spend time with their patients. She was right to find another provider who could give her what she wanted.

For me, being a non Five-Element practitioner, I've been on the receiving end of the Five-Element rap too many times. As I have found it, the problem really lies with the Five-Element side of the fence. Yes, the TCM side has regularly bashed the Five-Element side, but a lot of that comes from being grossly put down, over and over. Very often I've heard that only the Five-Element practitioner knows how to treat the mental-emotional sphere, that only they know how to diagnose deeply, that only they do real acupuncture. The TCMers are shallow and incomplete in their treatments, and only interested in symptom relief, not true and deep healing.

Therefore, the Five-Element practitioners are naturally superior and more useful to patients. In talking to Five-Element colleagues over the years, it seemed that this perspective was institutionalized by their leader, Dr. Worsley. I heard it so many times and for so long, it was like a mantra and after finding out that he thought this way, it made sense that it must of been part of the training program. Why this was so, I don't know, as it really didn't serve any purpose, and caused a lot of division that was unnecessary. I don't think it's that way now, but I'm not sure. I know a fair number of Five-Element practitioners no longer think this way, and some who are trying to reform this attitude. Lonny Jarret sees both styles as being on a continuum.

It was especially hurtful when finding out that they used a weird point and channel-numbering system that doesn't match any other style, they used terms and point names that don't show up in the literature and history (i.e., circulation-sex for Heart Protector), they used a simplistic pulse system, they eschewed herbs, and their ex-patients would come in pontificating about how they understood Asian medicine, but only the "five elements." All in all, it seemed kind of cultish and divisive.

I hope now that the Five-Element schools are more grown up in their teachings about the vast varieties and competencies of the other styles of Asian medicine, and no longer inculcate the superiority of their style. In my view, the whole of this medicine is a wheat field the size of Kansas, and the old-school Five-Element approach is a low hill where the adherents are busy holding up signs saying: "We're number 1 and the only true style."

All styles of Asian medicine work great, and the Five-Element Worsley style is just one of many. I applaud all the great work they have done, all the wonderful treatments and healings performed and all the patient education. But please, drop the superior attitude. Let's work together for the profession and let's get on with healing the world.

Stephen Schachter

via e-mail

What's In A Name?

I applaud Will Morris for raising an important topic and his call for discussion ("What's In A Name?" July 2010;11[7]). As Will pointed out, it is important that we reach a consensus on our titles and how we refer to our medicine so that we can move forward in branding our profession for the purpose of educating the public about who we are and what we do. Having just served as Chair of a public education task force for the AAAOM, I have a particular interest in the subject of branding. I hope to continue working with the leadership of our profession on developing a public education campaign, but can tell you we must solve this issue of what we call ourselves before real progress can be made in that effort. It would be counter-productive to devote resources to public education, make progress and then try to re-educate due to a name change.

Considering the above, I hope the profession will settle this issue one way or another as soon as possible. I believe it is especially important for our colleagues of Asian ancestry to lead this discussion. If a consensus can be reached among that cross-section of our profession, I am sure the rest of us will support that recommended language.

Matthew D. Bauer, LAc

via e-mail

Brown Rice Cuts Diabetes Risk

As health care providers who often provide nutritional counseling, it is vital that we provide the best nutritional advice available to our patients. I am concerned that the recent article describing some health benefits associated with brown rice fails to mention other factors that must be considered when evaluating the full nutritional value of this food.

Brown rice is high in a substance called phytic acid, a compound in seeds, grains, nuts and legumes that stores phosphorous until it is needed in the germination and sprouting processes. In this form, phosphorus is not bioavailable to humans. In addition to making phosphorus unavailable, phytic acid also binds to other minerals and therefore prevents their absorption in the digestive tract. For example, calcium, magnesium, iron and zinc absorption are all reduced by the presence of phytic acid. Additionally it can reduce the activity of our digestive enzymes, further reducing nutrient absorption.

In order to prevent malnutrition due to its high binding capacity phytic acid must be broken down by phytase. While some animals are able to produce phytase in sufficient quantities, humans are not. Traditional cultures often refine their rice or other grains at least partially in order to remove the outer layer of the grain, which is where the phytic acid is located. Other preparation methods mimic the conditions in which seeds sprout, such as soaking in warm water. Often these foods are also soured, which further reduces the phytic acid content and increases the quantity of other nutrients. In order to maximize the nutritional content of brown rice and promote absorption of other nutrients, brown rice needs additional preparation beyond simple cooking. This improves not only the nutritional profile of brown rice; it also improves its texture noticeably.

For more information on this topic, I recommend an article published in the Spring 2010 edition of the Wise Traditions journal, by Rami Nagel.

Jeannette M Schreiber, LAc

via e-mail