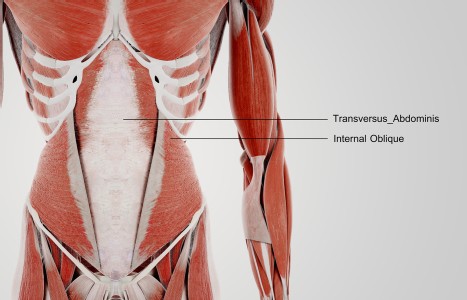

TrA-2, my primary needle location, I needle 95% of the time and I think it works the best. You’ll know you have the right point location when you discover the muscle twitching when applying electric stimulation.

Integrative View of Atopic Dermatitis

Before we can differentiate eczema according to TCM, we must define exactly what we mean by "eczema." "Eczema" and "dermatitis" are two terms that are often used interchangeably, but this is inaccurate and misleading and causes much confusion for patients and practitioners alike. "Dermatitis" simply means "inflammation of the skin" and refers to many types of inflammatory skin diseases. Skin inflammation that is also "eczematous" will have all of the following components: erythema (redness and inflammation), scale, and vesicles. So "eczema" (or "eczematous inflammation" or "eczematous dermatitis") can refer to any of a group of non-infective inflammatory reactions of the skin that have erythema, and develop scales and vesicles. It is an acute, subacute or chronic (relapsing) inflammatory skin condition that is characterized by itching (pruritis). The lesions range from pink to red, and when scratched will become weepy and crusted. As the condition progresses, dryness of skin becomes more predominant and lichenification (hyperplasia of the skin) can occur due to repeated scratching or rubbing of the sites.

The most common forms of dermatitis (some of which can be eczematous) are: contact dermatitis (includes irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis due to plants, and non-allergic contact dermatitis), atopic dermatitis (this is the dermatitis most commonly referred to as "eczema"), dyshidrotic eczematous dermatitis (a type of hand and foot dermatitis, a.k.a. "Pompholyx" or "vesicular palmer eczema"), neurodermatitis (a.k.a. lichen simplex chronicus), seborrheic dermatitis (a.k.a. "cradle cap" in infants), and photodermatitis. Photodermatitis refers to inflammation of the skin that occurs when a topically applied substance is then exposed to sunlight. This includes phytophotodermatitis (a skin reaction from exposure to plants and sunlight) as well as phototoxic and photoallergic dermatitis.

Of the above-mentioned types of dermatitis, the types that most popularly get referred to as "eczema" are atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. Arguably, most dermatologists will reserve use of the term "eczema" to be used interchangeably only with atopic dermatitis. This distinction is made because underlying cause of each of these conditions is completely different and they have different long-term effects. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV (cell-mediated, delayed) hypersensitivity reaction and the inflammation in the skin can be completely healed as long as exposure to the offending agent is identified and avoided. Atopic dermatitis/eczema, however, has a much more complicated etiology (multiple underlying causes) and may possibly be associated with type I hypersensitivity (which is an immediate IgE antibody response). Atopic dermatitis (AD)/eczema tends to become a chronic condition and is much more complex to treat. This is the condition referred to as eczema that you will see most commonly in the clinic. The condition usually begins in infancy (though it can manifest anytime) and may continue to recur in adulthood.

Diagnosis of AD/eczema is made based on clinical presentation, patient history, and (possibly) blood tests since IgE serum levels are elevated in many cases (though this is not a definitive criteria). But be alert: many patients will come to you with a diagnosis of eczema (usually from their general practitioner) that is not truly atopic dermatitis (AD). If it turns out that they actually have contact dermatitis and the causative substance can be found (though this may take some serious detective work), their rash can be resolved much more easily and you can spare them possibly years of frustration and discomfort. Be sure to take a thorough health history of your patient so you do not make assumptions and so you perhaps can flush out what other practitioners may have missed.

Etiology Of AD/Eczema

The etiology of atopic dermatitis/eczema is not clearly understood from the western biomedical perspective. In most cases AD/eczema appears in infancy. Though there has been no proof yet that AD/eczema is inherited, studies show that babies are more than 80 percent likely to develop it if both parents have it. Developing AD/eczema after the age of 20 is relatively uncommon though still possible.

According to the National Eczema Association, it is estimated that over 30 million Americans suffer from this form of eczema. Though the exact cause is unknown, approximately 85 percent of people with eczema are found to have elevated serum IgE levels. IgE antibodies in the blood indicate that eczema seems to be the result of a Type I hypersensitivity response. Type I hypersensitivity is a type of immediate allergic response. For reasons that are poorly understood (scientifically), some people are predisposed to having allergic reactions (respiratory, eye, digestive or skin symptoms) to substances that do not cause a reaction in other people. So people who develop AD/eczema also tend to have asthma and/or allergic rhinitis (seasonal or year-round allergies).

In many cases of eczema (especially in children), the itchy rash gets worse with exposure to certain foods such as milk, eggs, soybeans, fish and wheat. Inhalants, like dust mites or pollen, that cause other allergy symptoms (like sneezing, runny/stuffy nose, itchy eyes, sore throat), can also cause eczema to flare. Another factor that may be involved with the cause or exacerbation of eczema is Staphylococcus aureus bacteria. "Staph" bacteria are present on our skin in normal concentrations all the time.

In acute flare-ups of eczema there is often a much higher number of staph bacteria present on the skin. These bacteria secrete toxins that seem to act as "super-antigens" (substances that cause the body to produce antibodies in response to their presence) and result in an immune response that produces inflammation and makes the eczema worse.

Other factors that exacerbate or trigger eczema: skin dehydration (like from frequent bathing, over-washing of hands, dry climates), hormonal changes (like pregnancy, menstruation, thyroid problems), infections (staph, streptococcus, herpes simplex, candida), unfavorable external conditions (dry or cold weather), physically irritating fabrics (esp. wool clothing or blankets), and emotional stress.

Factors that exacerbate or trigger eczema:

- Milk

- Eggs

- Peanuts

- Soybeans

- Fish

- Wheat

- Dust mite allergies

- Pollen allergies

- Over-washing hands

- Frequent bathing

- Pregnancy

- Menstruation

- Thyroid imbalances

- Infections (staph or strep or herpes simplex)

- Dry, cold weather (decreased humidity)

- Sweating

- Wool clothing or blankets

- Emotional stress (this is not a cause of eczema, but certainly makes it worse)

Phases Of AD/Eczema

There are a two of ways to categorize the phases (stages) of eczema: by patient age and/or by duration of illness.

By patient age:

- Infant Phase (under age 2): Babies rarely are born with eczema, but the first signs of AD/eczema typically appear by the third month in infants. Babies with rashes should always be evaluated by a physician (preferably a dermatologist) and in this case it is helpful to differentiate eczema from seborrheic dermatitis ("cradle cap") and from miliaria rubra ("heat rash") since we use different herbs for each case. In the infantile phase of eczema, lesions most often appear on the cheeks, forehead and scalp, though may include the limbs and torso. It often shows up in winter as dry, red, scaly cheeks or chin (which tends to get more irritated due to drooling and wiping). It can look like the cheeks got rosy from sudden exposure to cold, but the redness does not go away. Itchiness can lead to scratching, which worsens the lesions. They can become crusty and the discomfort from itching can lead to much crying and disturbance of sleep for the baby (and subsequently, the parents!).

- Childhood Phase (age 3 to age 12/puberty): In this phase lesions most often are seen in the creases at the elbows and knees, around the neck, and at wrists and ankles. Poor eating habits begun during this phase make it more likely that the patient will continue to suffer eczema during adolescence. Scratching must be avoided so the tender skin does not become lichenified and so the rash does not become significantly worse.

- Adolescent/Adult Phase (puberty to early 20s and beyond): The lesions are most often found in the creases at the elbows and knees as well as around the neck. Skin becomes drier and thicker where scratched. Commonly, hands become involved after coming into contact with irritants or with hand washing that occurs much more frequently than in the earlier phases. Inflammation of eyelids often develops since the skin is so delicate and frequently gets rubbed subconsciously.

By duration of illness:

- Acute eczema (original onset or an acute flare-up): Original onset of AD/eczema typically occurs in infancy and most cases appear by the early 20s. Acute flare-ups can occur at any time during the course of the disease. Various types of skin lesion may be present during this phase: erythema (redness and inflammation), papules (tiny bumps), and vesicles (little bumps filled with fluid). During this stage, lesions are progressing in severity of symptoms, growing in number, and/or covering a larger area or more areas of the body. The lesions can quickly become infected, especially with frequent scratching.

- Subacute eczema: In this phase, there is less redness and swelling, fewer vesicles or less exudate, smaller papules (bumps), and more dryness developing. Subacute eczema can revert back to the acute stage if it becomes more severe or it can linger on to develop into chronic eczema.

- Chronic eczema: This stage occurs when the illness has existed for some time. The lesions are drier, thicker, rougher, have scaling, and there may be more fissuring or cracks in the skin (or accentuation of the creases in the palms of hands). Lesions may stay hyperpigmented (darker) or hypopigmented (lighter) after healing.

In Part II of this article we will examine the etiology of AD/eczema from the perspective of TCM, as well as TCM pattern differentiation.