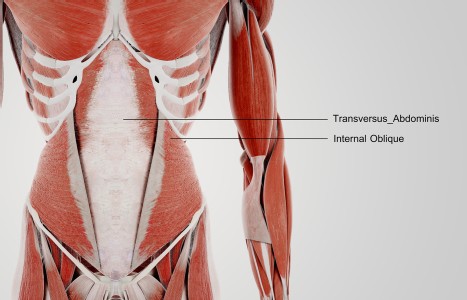

TrA-2, my primary needle location, I needle 95% of the time and I think it works the best. You’ll know you have the right point location when you discover the muscle twitching when applying electric stimulation.

Whose Energy Is This Anyway?

Do you ever feel that you have taken on someone else's energy? I'm not wondering if you are psychotic. I just wonder if you ever feel that you are sometimes so influenced by others, that you act in ways that are foreign. I hear about this all the time when I work with people in organizations.

When asked how he manages to stay upbeat all the time in front of his employees, a organizational leader told me, "Oh, I'm not this way at home. I can collapse there. In fact, my wife calls me a 'couch potato,' not a term they'd ever use at work!"

When this fellow goes to work, he's "on" He moves quickly, adds momentum to projects and is regarded as a "doer." Then he goes home and switches "off." At work, he drives and thrives. At home, he collapses, or so it seems. What is going on?

Our subject, Dr. Doug, understands that his job as a leader is to set direction, manage the performance of his subordinates, and protect them from organizational dynamics that may impede good work. Another part of his role is to contain anxiety about the organization that might infuse into his team.

He "contains" a lot of information that he can't share. Sometimes it's positive news that isn't ready to be made public, but more often, Doug's body and mind are sponges soaking up organizational information and holding onto it for a while. If this "held" information will result in conflict, loss, humiliation or change, he anticipates a difficult future. A seasoned leader, he absorbed pressure for years that he cannot distribute to others.

Usually an upbeat guy, ready to mediate and resolve difficult staff issues, Doug is a leader who creates solutions to problems and keeps people motivated. Other doctors in leadership roles often ask for his counsel with complicated and weighty staff or administrative matters. Like a chef expertly wielding a carving knife, Doug is known for paring out simple, clean and utterly palatable solutions.

Prior to the recent recession, his hospital and his practice thrived. Recently, however, Doug's health care system "downsized, " cutting about 6 percent of the staff. His practice, formerly 14 physicians, six nurses, two physicians assistants and three office managers, lost a nurse and reduced the manager's hours. Anticipating cuts months before they occurred, Doug could not tell the team until the hospital had completed its planning for the rest of the organization.

I asked him how he felt during that time. "Sluggish," he answered. We talked about what may be contributing to his loss of energy.

I asked if any of his personal or professional routines had changed. "I've been eating more carbs at night, " he answered. "And I'm not sleeping well. I know we will be cutting Mary's position and I'm worried about her. I wake up in the middle of the night wondering if there's any way I can save her job, so I go upstairs to my home office, and do e-mails and eat pretzels to dull my senses." In fact, Doug put on six pounds during three months, eating from anxiety. Ironically, both he and the organization needed to reduce.

He is not unlike many leaders I know who unconsciously embody organizational dynamics. When the system is doing well, they do well. When the workplace is in decline, they have trouble with their energy and health.

In Doug's case, you could say that carbohydrates were a culprit behind his loss of energy. You could also say that sleep deprivation led to a slower metabolism and less efficiency. Doug didn't mention that he got a sinus infection that lingered for months during the time he was planning the staff reduction. Less sleep and more organizational stress often leads to lower immunity.

We expect our leaders to have answers, but we rarely worry about their health. When the hospital needs more energy, Doug contributes his own. Thus in times of change, when the system needs more energy, he is tired. As the leader uniquely responsible for staffing, he has contained a sense of loss, living for months with the knowledge that jobs would be lost but unable to confide this to anyone. Eventually, the team as a whole will also feel the loss, at which point, oddly, Doug will feel better, releasing the "contained" energy.

American mythology about leadership glorifies the individual. We think of George Washington heroically forging across the frozen Delaware River, gallantly standing in the front of a rowboat. A face of stolid determination. No apparent thought of failure. Or Abraham Lincoln, nobly addressing the nation, taking an eloquent and unpopular stand against the division of the union. Willing to sacrifice his political career to save the nation.

Leaders, however, are only as potent as their followers allow. Like grand masters of the martial arts, great leaders know how to build energy, contain it just long enough to let it ripen and then use it for the benefit of the organization. In the process of holding it, however, they often get sick. The back story is that the public gets their best while their families and caregivers put them back together. Leaders are only as good as those they lead. If either suffers, both are likely to lose energy. Their fates are entwined.

Group dynamics and team experts know that this is true. In their landmark book, The Visible and Invisible Group, psychologists Yvonne Agazarian and Richard Peters brilliantly described how small groups are systems, employing all team members to keep the work of the team going. When too much emotion creates a risk of a loss of productivity, an individual may "contain" energy that is really that of the group; much more powerful than one's own energy.

During the 1970's, psychologists pioneered work applying General Systems Theory to families. Salvatore Minuchin, a family therapist, developed Structural Family Therapy, which addresses problems within a family by charting the relationships between family members or between subsets of family. These charts represent power dynamics, as well as the boundaries between different subsystems. The therapist tries to disrupt dysfunctional relationships within the family and cause them to settle back into a healthier pattern. I have seen wonderful applications of this method to work teams which have distinctive subgroups.

Along with Dr. Virginia Satir's Family Systems Therapy work, Minuchin, Agazarian and Peters all understood that a group, whether it's a family or a team, share a common energy. The sum of the parts does not equal the whole. Rather, the whole has its own energy. When something happens to challenge the well-being of the whole, however, individuals may step up and absorb more energy than they have on their own.

If you think of the team as an elephant, and a team member as part of it, imagine how an individual feels if the elephant has a heart attack? Or an anxiety attack? So, when Doug stopped sleeping, overate, and got a three-month sinus infection that didn't quit, at the same time that his once flourishing organization admitted to the equivalent of failure, whose energy was he feeling? An elephant who realized it wasn't immune to change? Or a successful doctor who couldn't shield his team from changes.

Chinese medicine understands that individual energy relates to the outside world. In fact, the outside world affects specific, diagnosable energies. Like Eskimos who have a plethora of names for snow, Chinese medicine defines dozens of types of energy. Wei qi, commonly understood as "protective energy," defends the person from pathological environmental influences. Loss of immunity often comes when wei qi is weak. People are more prone to get airborne infections and equally likely to recover slowly. Loss of sleep encourages weak wei qi.

Chinese medicine defines another type of energy that is often damaged in leaders: the shen. Associated with the heart, shen is considered to be the aspect of a person relating their identity (their core personality) to the larger universal energy. Some writers call this "heart spirit." Disturbance of this energy often leads to night time anxiety, vivid or disturbed dreams, and a waking state in which one's sense of equanimity is upset.

Assuming that the hospital reduction hurt the staff sense of pride and stability, we assume that the change depleted energy, particularly wei qi and shen. Knowing this, we might have tried to build up these energies in the team while waiting for the change. Building energy can help you avoid depletion. Prevention - i.e., intentionally adding to the team's capacity prior to a change - might have avoided later problems.