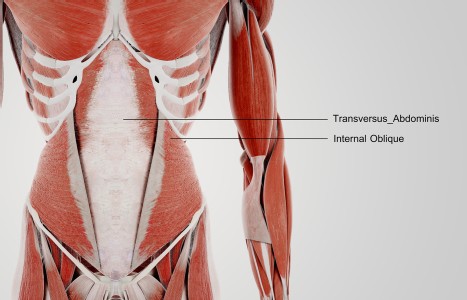

TrA-2, my primary needle location, I needle 95% of the time and I think it works the best. You’ll know you have the right point location when you discover the muscle twitching when applying electric stimulation.

Healing Trauma: Cultivating Resilience and Presence Through Mindfulness, Part 1

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. – Henry David Thoreau

In the quote above, Thoreau touches on one of the fundamental issues of being human — due to fear of pain, suffering, alienation, and lack of love, many people end up shutting down emotionally, spiritually, and even physically, becoming disconnected, both within themselves as well as disconnected from the world around them. All humans, by the very nature of being human, will experience moments of trauma and suffering. What, then, makes the difference in how the individual who experiences trauma, suffering, and spiritual loss reacts to such experiences? Why do some individuals shut down and enter a state of quiet desperation, while others emerge from such difficulties appearing to be even more present, whole, and actualized human beings? In other words, what prevents or allows an individual access to deep levels of resilience, and therefore the ability to use difficult and painful experiences as opportunities for growth?

The Nervous System and Embodiment

To explore these questions, I will intentionally mix metaphors by interchangeably using Western and Eastern perspectives and language. While this may not be the most exacting or rigorous method, it is my hope that in losing a small degree of exactitude we may gain greater insights into the multidimensional aspects of the human experience. After all, there is no single perspective that can ever encapsulate the totality of the human experience; therefore it is through combining multiple perspectives that we may generate a form of triangulation of understanding that more closely approximates the dynamic aspects of being human. In this first section, I will summarize the Western and Eastern medical metaphors that I will draw on throughout this paper.

In Eastern philosophy and medical practice, humans are seen as a coming together of yin and yang, or body and spirit. When trauma occurs, the spirit "leaves" the body, for it does not want to be present to the experience of the trauma. In such instances, the individual tends to be less present; they are disconnected within self as well as disconnected from the world around them. This may last a moment, or many years, depending on the individual, the severity of the trauma, and how they handle the experience and the recovery. Conversely, when the spirit is fully grounded in the body, the individual tends to be more experientially present, healthy, and actualized, as well as connected to those around oneself. And this is circular — when one feels more connected to those around oneself, the spirit becomes more fully grounded in the body. According to this perspective, much of the ability to heal, as well as capacity for spiritual resilience, occurs through practices that work to ground the spirit in the physicality of the body.

We can draw a relationship concerning this interaction between spirit and body with understandings of the autonomic nervous system in Western physiology. In this perspective, the autonomic nervous system is often divided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system is the fight-flight-freeze aspect, while the parasympathetic nervous system is the rest-digest-heal aspect. When trauma (or fear of trauma) occurs, the sympathetic nervous system is strongly activated, and the individual's awareness moves upward and outward — they become hyper-aware of their surroundings and possible threats, they become less sensitive to sensations in the body, and they become ungrounded. Conversely, when the parasympathetic nervous system is strongly activated, the individual is very grounded within their body — the body's awareness is directed internally and is focused on resting, digesting, and healing.

However, it is important to note that these are not exact correlations, nor are the two aspects of the dialectic within each tradition simply polar opposites. Going further, it is also not the case that one state from either perspective is inherently desirable and the other undesirable — in the natural state, one should have a natural movement between the two: being grounded in the body at times and not being as grounded at others, as well as being in the sympathetic nervous system at times and in the parasympathetic at others. Both the movement into the sympathetic nervous system as well as the spirit leaving the body can be a natural and healthy defense mechanism in times of stress and trauma. It is only when one becomes stuck in such a state that it can be considered pathological. And this is precisely the reason for introducing these perspectives — in cases of severe trauma, loss, and spiritual crisis, commonly the individual is stuck in a place of the spirit not being grounded in the body, as well as stuck in a hyper-sympathetic response. Using this framework, we can now turn to examine methods and techniques for caregivers to use in approaching individuals undergoing such an experience.

Presence

This is the key to healing and transformation. There is a seeming paradox that occurs when people experience severe pain, trauma, difficulty, and spiritual crisis—the often natural and inherent response in such times is to try to escape, to try to avoid feeling the pain, distress, and anguish that accompanies such moments. The spirit wants to leave the body, and does not want to be present. Similarly, the sympathetic nervous system kicks in, adrenaline is released, and the likelihood of fear, anger, or other strong (and possibly unhealthy) emotions and reactions is increased. And yet, when we try to escape, when we dissociate from the lived experience of the moment, when we react from a place of anger or fear, then we begin to encapsulate and concretize those very fears, sufferings, and traumas that we are trying to escape. In other words, when the spirit is not grounded in the body, stasis occurs; it is when we react from a place of fear that our fears most often come true. Although it is painful and difficult, often the only way to truly heal from such experiences is to bring presence into them — whether it is at the time that they initially occur or when they are triggered three months later, three years later, or 30 years later.

From the Eastern perspective, presence occurs when the spirit is fully grounded in the body, and the more inter penetration there is between body and spirit, the greater the degree of presence. This is something that we all have access to, at all times — in fact, it can be considered our natural state — it is just a matter of cultivating the ability to be more fully present, and it is through cultivating this ability that we find freedom and peace. How, then, does one cultivate such presence?

There are many techniques and methods that can be used to help someone become more present. One of the foundations of presence is mindfulness, which is often cultivated through meditation and other body-mind awareness practices. Mindfulness is thus a fundamental practice to help an individual become more present to their experience. It is a way of learning to directly perceive the experiential, moment-by-moment play of life, which is also how we heal. However, in order to allow space for such mindfulness to occur, one has to let go of trying to control their experience, and to simply experience what is there. When this happens, the individual is able to become more fully present to the reality of the lived experience, rather than living in the conditioned state of mind. Clearly, mindfulness can be a powerful ally in helping one to move more fully into the present moment. However, given that it is precisely during the times when we most need mindfulness and presence (i.e. when experiencing the pain, fear, and dissociation that occurs with trauma and adversity) it is most difficult to be mindful, how does one learn to practice mindfulness at such times? We will turn to examine this question in the second part of this article, stay tuned.